Over the past two centuries, life expectancy in Canada has more than doubled, rising from under 40 years of age to almost 82, thanks to improved public health, strengthened infrastructure, and better access to healthcare.1 This is a tremendous success story. But according to research from the McKinsey Health Institute (MHI), those extra years may come with limitations, leaving individuals unable to live independently, work, or pursue hobbies—whether physical, such as hiking or ice skating, or mental, such as card games or chess.

In this new analysis, MHI finds that Canadian women spend 24 percent more time than men in poor health and with varying degrees of disability. In Canada, out of every 100 people, women will experience about 14 years lived with disability, compared with 11 years for men—roughly 24 percent higher. This affects her ability to be present, productive, or both—at home, in the workforce, and in the community—and reduces her earning potential (see sidebar “Terminology used in this article”).

Building on previous work from the McKinsey Health Institute and the McKinsey Global Institute, analysts quantified this health gap in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and the extent to which this difference results from the structural and systematic barriers women face (see sidebar “Research methodology”).

Addressing the 24 percent more time that Canadian women spend in poor health relative to men not only would improve the health and lives of millions of women but also could boost the Canadian economy by at least $37 billion annually by 2040. This estimate is probably conservative, given the historical underreporting and data gaps in women’s health conditions, which undercount the prevalence and undervalue the health burden of many conditions for women.

Whereas Canada ranks among the top ten countries globally for gender equality and is the ninth-largest economy,2 it represents the fifth-worst women’s health-related economic gap as a share of its projected 2040 GDP, behind Australia, France, Germany, and Japan.3 This means Canada has an opportunity to build a stronger economy based on healthier women. Similar to prior published work by McKinsey on the power of parity, women’s collective contribution to the labor workforce is a major driver of this value and impact.

It also reflects Canada’s goal of seeing all its people strive for their full potential in health, productivity, and inclusion. Now is a once-in-a-generation moment to address decades of women-agnostic healthcare that has left long-standing impacts on Canadian women’s lives. The women’s health gap has emerged as a critical frontier for equality and economic opportunity.

The health gap: Women are disproportionately and differently affected by the top health conditions

Tackling women’s health means understanding that their biology is uniquely different from men’s, beyond differences in reproductive organs. Globally, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) account for only 5 percent of the women’s health burden.4 Comparatively, when looking at specific conditions affecting Canadians, more than half of the top ten conditions affect women disproportionately or differently—this means there may be a higher prevalence in women compared with men, or a higher disease burden. For example, cardiovascular conditions can vary between men and women: Heart attack symptoms, for instance, present differently, with reports by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada revealing that early heart attack signs were missed in 78 percent of women5 (Exhibit 1).

The economic impact: Canada could unlock $37 billion in GDP

Women’s health and productivity are deeply interconnected. Poor health reduces economic participation, which in turn lowers income and worsens access to healthcare—creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates the health gap. The McKinsey Health Institute, in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, finds that closing the global women’s health gap could allow women to add 1.7 percent to global GDP.

The direct economic impact of the women’s health gap was calculated using population and workforce predictions up to 2040. Health gains were converted into labor force involvement and productivity, while economic gains were estimated through four avenues: fewer health conditions, expanded participation, increased productivity, and fewer early deaths. The direct impact in Canada is staggering: $37 billion6—almost equivalent to the GDP generated by agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting—and this figure excludes new emerging areas such as endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome.7 For context, a recent McKinsey publication, “The potential benefits of AI for healthcare in Canada,” noted that the net savings opportunity that could be generated for the Canadian healthcare system in the near term by using AI at scale is $14 billion to $26 billion, increasing affordability without negatively affecting outcomes and experience. Closing the women’s health gap is higher, sizable, and achievable.

Canada is also at an inflection point for productivity and workforce participation: It was previously a global leader in GDP per capita but now experiences the slowest economic growth among the G7.8 While the McKinsey Health Institute has previously positioned Canada as a “worker-advantaged country,” a recent report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information has demonstrated the wide variability across provinces and domains, underscoring increasing risks of worker shortages.9 If these trends are not dramatically reversed, Canadians may face a much lower standard of living and a reduced capacity to fund national priorities, including a strong social welfare system, climate adaptation and resilience, and commitments to peace and stability, among others.

Exhibit 2 illustrates the four drivers of closing the health gap: fewer health conditions, expanded participation, increased productivity, and fewer early deaths.

Canada stands out as a major economy with a disproportionately large women’s health gap in raw economic terms, ranking as the fifth-largest loss globally, as a percentage of GDP, when measured as a share of projected 2040 GDP (Exhibit 3). This places Canada among the countries with one of the largest gaps compared with most other G7 peers, including the United States, and close to high-gap countries such as Australia and Japan. However, when adjusting for GDP per capita and economic output per person, the relative gap shrinks, resulting in Canada dropping to 16th. This means Canada ranks among the top five largest economies in terms of the absolute share of GDP lost to gender health disparities, yet it possesses one of the strongest economic platforms to close it. In a nation with the resources, systems, and talent to lead, leaving this gap unaddressed is not a matter of capacity; it is a matter of choice.

These rankings underscore not only the scale of the challenge but also the outsize returns available from even modest progress. In a global context, Canada has both the economic capacity and the healthcare infrastructure to move quickly, setting an example for other nations. By acting decisively, Canada can turn a systemic weakness into a competitive advantage—boosting labor force participation, improving workplace productivity, and fostering innovation in health research and care delivery. Moreover, progress here would reverberate beyond economics, strengthening social cohesion and demonstrating that investing in women’s health is an investment in national prosperity.

Notably, ten health conditions affect only, or disproportionately, women and contribute to about a third of the $37 billion GDP impact (Exhibit 4). Focusing on these conditions can offer a path to deliver improved health outcomes and significant economic gains. For example, closing the gap for premenstrual syndrome, depressive disorders, and migraine alone leads to a GDP impact of more than $6 billion on the Canadian economy.

The differentiated impact: Each province must consider its unique context

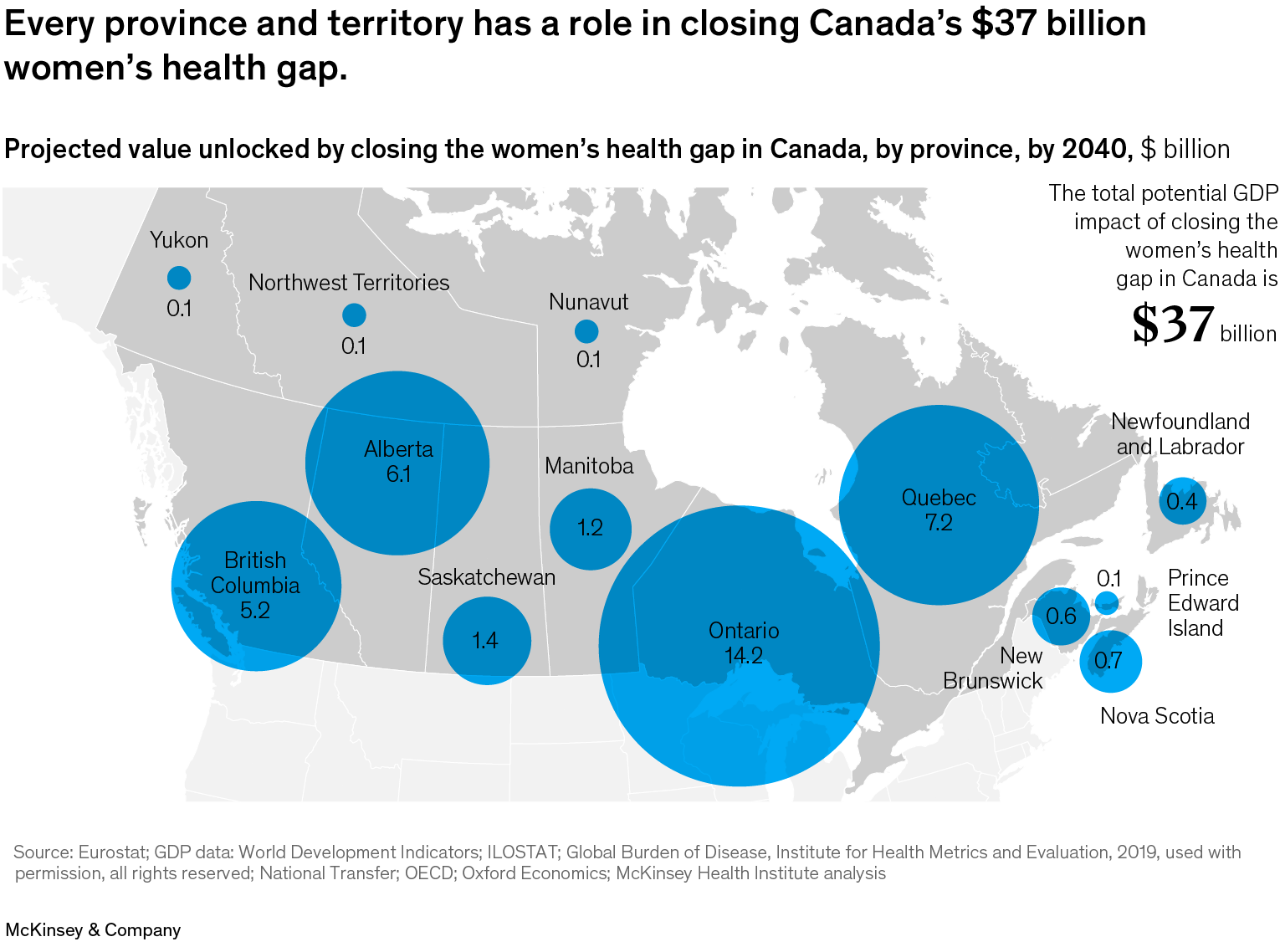

The $37 billion annual economic opportunity from closing Canada’s women’s health gap is not evenly distributed—but this variation creates room for smarter, more localized strategies. When accounting for women’s population size and age distribution, workforce participation rates, employment rates, and provincial GDP per capita, we find that Ontario and Quebec combined represent more than $20 billion in GDP potential, reflecting the scale and impact of addressing the health gap and their relative contribution to the Canadian GDP (Exhibit 5).

Alberta ($6.1 billion) and Saskatchewan ($1.4 billion) stand out with outsize gains relative to their share of the national population, pointing to opportunities for high-return investment in service delivery, condition-specific interventions, or access expansion.10 Opportunity in these provinces is driven by high participation of women in the labor force, despite lower employment rates and GDPs; when women are unable to work in these provinces because of health conditions, the GDP impact is greater.

In the Atlantic and northern regions, while the economic figures are smaller, the case for targeted action remains strong, particularly where rural access, aging populations, and equity considerations intersect. These regional patterns reinforce the need for tailored provincial strategies, matched to system maturity, demographic dynamics, and readiness to scale.

What’s driving the gap?

There are three root causes behind the disparity women face concerning their healthcare—efficacy, care delivery, and data—that must be addressed. Together, these factors shape how effectively women’s needs are understood, prioritized, and met. The biggest gaps in efficacy and care delivery for women in Canada are in cancer and cardiovascular diseases, together accounting for well over 200,000 DALYs by 2040. By improving these areas, Canada could not only unlock better health outcomes for millions of women but also strengthen the resilience of the healthcare system, reduce long-term costs, and drive inclusive economic growth through a healthier workforce.

-

The efficacy gap. Close to two-thirds of the women’s health gap in Canada is driven by an efficacy gap—specifically, in cancer and cardiovascular breakthrough interventions, cancer screening, hormonal therapy, mental health treatment, and psychological care. For decades, medical research and clinical trials have disproportionately centered on male biology, creating a “default male” model for diagnosis and treatment. Efficacy—the benefit measured under tightly controlled trials—has been derived largely from cohorts that underenrolled women. As a result, many conditions present differently—or go undetected—in women, leading to misdiagnoses, undertreatment, and slower innovation in female-specific health solutions. For example, acute asthma exacerbations account for more than 80,000 emergency visits across Canada annually, with symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, or chest tightness.11 Reports from Alberta demonstrate that, on average, women seek care at minimum 30 percent more often than men in the emergency department for asthma exacerbations.12 Closing the efficacy gap would accelerate breakthroughs in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment tailored to women’s unique physiological and hormonal profiles.

-

The care delivery gap. Differences in access, quality, and continuity of care disproportionately affect women, particularly those in rural areas, Indigenous groups, racialized communities, and lower-income groups. Half of the care delivery gap in Canada is driven by discrepancies in cardiovascular care: access to breakthrough interventions, surgeries, and appropriate pharmacological treatments. These disparities can manifest in delayed diagnoses, longer wait times, and fragmented treatment pathways. Racialized and minority women often face more advanced-stage breast cancer diagnoses due to screening guidelines that are not aligned with their needs;13 South Asian women in Canada are more frequently diagnosed at later stages compared with other groups, limiting treatment success;14 and women in rural and remote Indigenous communities face barriers to screening access.15 Additionally, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis women have historically faced higher risks of adverse birth outcomes than non-Indigenous women: While the overall mortality rate for Canadian infants was 4.4 per 1,000 in 2021, the Indigenous infant mortality rate was more than twice that: 9.2 deaths per 1,000 births.16

Moreover, gaps in perimenopause and menopause care continue to affect women profoundly, particularly during their working years. Menopause symptoms can be debilitating, with around 75 percent of women experiencing hot flashes,17 leading to impacts on productivity, well-being, and economic outcomes. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study estimated that menopausal symptoms cost US employers about $1.8 billion annually in lost work time.18 For roughly 20 years, many women and providers relied on guidance—now outdated—that tied hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to the risk of breast cancer or heart disease. Updated guidance on HRT’s benefits now highlights a need for more individualized approaches.19

Another important factor in achieving equity in care delivery is that a fifth to a quarter of women aged 15 and older in Canada were immigrants, meaning they were born outside the country.20 While evidence-based approaches can address a diverse set of problems, care delivery and knowledge sharing should ideally be culturally sensitive.21 Enhancing care delivery to be more inclusive, coordinated, and responsive to women’s needs could dramatically improve outcomes while easing strain on acute care services. This is critical for girls too, given emerging evidence around period poverty.22

-

The data gap. Women’s health is hampered by a lack of comprehensive, disaggregated, and longitudinal data. Without it, researchers and policymakers cannot fully understand disease patterns, evaluate interventions, or identify where resources are most needed. While CIHI’s recent Shared Health Priorities initiative—in collaboration with federal, provincial, and territorial governments; Statistics Canada; Canada Health Infoway; and Integrated Youth Services—is a start to developing comparable cross-provinces indicators, women-specific data remain a gap.23 Closing the data gap would unlock new insights, catalyze targeted innovation, and enable policy decisions that deliver measurable, sustained improvements in women’s health. The latest Health Canada Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis Plus Action Plan 2022–2026 aims to strengthen Health Canada’s systematic integration of sex, gender, and diversity considerations, but certain enforcement mechanisms (for example, grant allocation, drug, or device approval) continue to lag behind OECD peers, such as the United States.24

A call to action

Addressing the women’s health gap presents a meaningful opportunity for Canada. Over half of the additional healthy life years accruing to women and 75 percent of GDP gains materialize during working years. Women create powerful ripple effects in communities: They make up the majority of teachers (up to 75 percent),25 nurses (up to 90 percent),26 and caregivers—roles that enhance the productivity of others and strengthen long-term investments in education and health. Women philanthropists also invest differently, tripling their donations since 2011 and seeking clear impact, especially for women and girls.27

Recognizing the vast potential to improve the lives and livelihoods of half of the Canadian population—while boosting the economy—serves as the catalyst for closing the women’s health gap. Fourteen major actions can catalyze impact, and every facet of this effort requires commitment from healthcare leaders and research institutions, policymakers, innovators and businesses, investors and philanthropists—and from each citizen working side by side (Exhibit 6). In this endeavor lies an opportunity worth $37 billion in economic potential driven by improved women’s health and economic participation—not factoring in the emerging opportunities in new markets (such as femtech). The question is not whether this wealth of opportunities exists, but who will take the initiative to seize it and drive change.

Canada needs a blueprint to move the needle on the women’s health gap. While the gap is vast, change can begin by tackling specific diseases and conditions at a national or provincial level. By closing this chasm, women can become healthier, and the economy can experience long-lasting, beneficial ripple effects, including fewer health conditions, expanded participation, increased productivity, and fewer early deaths, benefiting women, their families, and their communities. Closing Canada’s women’s health gap is not a cost—it’s the smartest investment the country can make.

To read this report in French, click here.