The 2025 Los Angeles wildfires were among the most destructive in California’s history, displacing tens of thousands of residents and causing economic losses projected to exceed $100 billion. Yet they are only the latest chapter in an escalating trend: Since 2017, eight of the top ten US wildfire events in terms of highest insured losses occurred in California.1 This pattern underscores how rapidly wildfire risk in California has intensified, signaling an escalation in both the scale and frequency of events with extreme losses.

The recent fires have further exposed longstanding structural issues in California’s $15 billion homeowners insurance market, the largest in the country. Much of the risk has historically been mispriced, leading many major carriers to scale back their footprint or withdraw from portions of the state over the past several years. Fewer options for insurance, particularly in high-risk areas, have caused homeowners to lean more heavily on the state’s Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan, the insurer of last resort.

California had already started implementing structural reforms before the recent fires. Most notably, its Sustainable Insurance Strategy seeks to modernize rate-setting tools and regulatory requirements by introducing forward-looking wildfire models, incorporating net reinsurance costs, and strengthening rules around insurer obligations in high-risk zones. These reforms represent important early progress, but the scale of California’s wildfire risk points to the need for even more significant action. Today, California’s private homeowners insurance market is facing a coverage shortfall of $1.35 trillion to $2.00 trillion, the gap between total wildfire risk exposure and current available financial protection through private insurance and the state’s FAIR Plan. Approximately one-third of that total is in concentrated zones with the highest wildfire risk. By our estimates, addressing these issues and putting the market back in balance—with all fire risk fully covered—would require an infusion of $8 billion to $10 billion in additional annual premiums at a time when homeowners are already struggling to afford insurance.

To strengthen long-term resilience, California could focus on two strategic areas: First, it could improve insurance coverage through active risk reduction. Potential levers include updating infrastructure and building codes, integrating risk into land use planning, and further scaling vegetation management near the wildland–urban interface. Second, the state’s stakeholders could seek to better optimize risk ownership and risk financing to provide financial coverage on a larger scale. Measures could include expanding access to alternative capital, rebalancing risk through public–private mechanisms, and supporting innovation in insurance products that reward proactive risk mitigation. As ongoing market reforms go into effect, aligning premiums more closely and swiftly with underlying risk could also help strengthen the insurance system’s financial sustainability and reinforce incentives for risk reduction.

Given the high level of risks, the large geographical footprint, and the amount of capital at stake, making progress will require a large-scale concerted effort. A successful effort would protect many more Californians and could become a “lighthouse” for other states and countries facing extreme events.

The Los Angeles wildfires magnify structural market challenges

In January 2025, Los Angeles experienced the most catastrophic wildfire disaster in its history. The fires burned more than 50,000 acres, claimed at least 29 lives, and destroyed upward of 16,000 structures.2 Insured losses are projected at $35 billion to $45 billion.3

California has responded to the unprecedented devastation with a concerted recovery effort. Within 30 days after the wildfires, hazardous debris was cleared from more than 9,000 properties affected by the Eaton and Palisades fires, the fastest removal operation in US history.4 Governor Gavin Newsom issued executive orders suspending permitting and environmental review requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act and the California Coastal Act, a move the governor’s office has described as “cutting red tape to rebuild Los Angeles faster and stronger.”5 In addition, the state enacted a $2.5 billion relief package to bolster emergency response, accelerate recovery, and support wildfire preparedness initiatives.6

Insurers have already paid out more than $20.4 billion in claims as of July 2025,7 critical capital that thousands of homeowners and businesses need to begin recovery. Reinsurers may ultimately cover 10 to 20 percent of this amount.8 However, the fires have also reinforced deeper structural strains in the market.

The state’s market for homeowners insurance faces three key challenges.

Historical constraints on risk-based pricing

As climate risk intensifies and disasters grow in scale, insurance pricing that better reflects the evolving nature of risk and associated costs could create more transparency on the true level of risk exposure and help to promote market participation by insurers. However, California’s regulatory framework, including Proposition 103, has constrained the ability of insurers to adjust premiums as the underlying nature of the risk evolves.

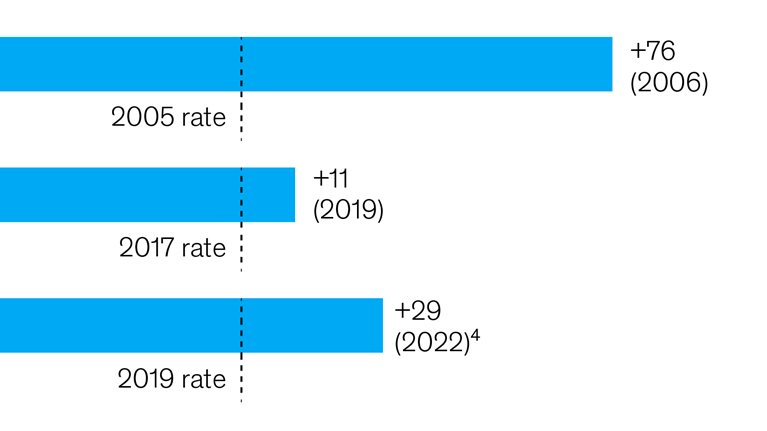

As one example, Proposition 103 requires the state’s Department of Insurance to hold a hearing on proposed rate increases above 7 percent for personal lines upon a timely request.9 In rate filings from 2010 to 2023, many insurers repeatedly requested increases just below the 7 percent threshold, suggesting that regulatory limits constrained filing requests even as underlying risk intensified.10

In addition, reinsurance costs, an essential component of insurer capital, have nearly doubled since 2017, with a 35 percent spike in 2023 alone.11 Until recently, to protect consumers against significant rate increases, California regulations prevented insurers from incorporating these rising costs into their rates, hindering their ability to price risk into policies for fire-prone regions.

California historically required insurers to base their rates on past wildfire losses, essentially prohibiting the use of forward-looking catastrophe models and excluding reinsurance costs from rate filings.12 Over the past several years, these restrictions helped preserve a degree of affordability for consumers in the short term, but they also prevented premiums from keeping pace with rapidly increasing wildfire risk, higher reinsurance costs, and rising construction expenses.13 For reference, the average annual homeowners insurance premium in California was estimated at $1,700 in 2023, below the national average of $1,800 and significantly lower than other states with high-risk profiles such as Florida,14 where annual premiums were more than $3,600, on average.15

The landscape began to shift in December 2024. California launched the Sustainable Insurance Strategy, which now permits the use of modern forward-looking wildfire risk models and state-specific reinsurance costs in rate filings—provided that insurers continue to write policies in wildfire-prone areas.16 The California Department of Insurance recently approved several of these models for use, marking an important step toward better aligning premiums with the fast-evolving wildfire risk.17 As rates begin to better reflect current and near-term risk conditions, adjustments are likely to occur gradually through the regulatory process. Further, the state has continued to expand a set of reforms to broaden FAIR Plan coverage (such as including coverage for manufactured homes), increase transparency, and strengthen oversight to support long-term market stability.18

Mounting strain on the state’s FAIR Plan

Even before the 2025 wildfires, California was experiencing a steady reduction in private insurer participation, particularly in high-risk wildfire zones. Following the 2017–18 fire seasons—which included the Thomas, Atlas, Tubbs, Camp, and Woolsey fires that triggered more than $30 billion in insured losses—major carriers began scaling back or exiting portions of the homeowners insurance market.19 The trend continued through subsequent fire seasons in 2020 and beyond. As a result, from 2019 to 2024, more than 100,000 homeowners lost coverage due to carrier exits and nonrenewals.20

With private capital pulling back, more homeowners have turned to the California FAIR Plan.21 Originally established to provide temporary coverage to those unable to obtain insurance through the private market, the FAIR Plan is carrying a growing share of the market’s wildfire risk: Its total exposure nearly quintupled over the past five years, reaching $700 billion in September 2025, with about 650,000 policies in force and nearly $2 billion of premiums collected (Exhibit 1). It is now the largest residual insurance market in the country, surpassing Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corporation.22 Enrollment in the highest-wildfire-risk areas has grown 12 times faster than in the lowest-risk zones during this period, further concentrating risk within the FAIR Plan.23

As the FAIR Plan assumes a greater share of the state’s highest-risk properties, it faces increasing operational and financial strain. Managing such concentrated exposure presents challenges in underwriting, claims capacity, and reinsurance procurement. The result is a potentially destabilizing cycle: Risk accumulates in the FAIR Plan, the need for reinsurance grows (and at levels that are more expensive to reinsure), and the funding gap gets worse. Under the FAIR Plan’s postdisaster recoupment process, participating insurers may bear indirect liability for FAIR Plan losses even if their own policyholders are unaffected.24 This added indirect exposure may raise costs across the state and, in turn, lead to additional private market exits or a reduction in insurance availability, further deepening reliance on the plan and amplifying systemic risk.

To address some of these pressures, the state recently authorized new financing mechanisms that allow the FAIR Plan to access additional capital, such as lines of credit or bonds issued through iBank, to increase liquidity and help meet claims obligations following major disasters.25 While these tools could ease short-term liquidity constraints by spreading the cost over time, they do not fundamentally change the plan’s fast-growing exposure. At the time of this article’s publication, the FAIR Plan submitted a proposal to increase home insurance rates by an average of more than 35 percent beginning spring 2026.

Widening private insurance coverage gap

Our research reveals that today, for wildfires alone, California’s single-family-housing market faces a private-insurance coverage gap of $800 billion to $1.3 trillion. This total includes both uninsured and underinsured properties and focuses only on single-family homes, which is a lower bound of the overall coverage gap.26 Roughly $300 billion of the total is concentrated in zones with the highest wildfire risk (Exhibit 2). Among these areas, the 10 percent of households with the lowest disposable income27 account for $65 billion of the insurance gap (approximately 22 percent), underscoring the disproportionate burden on financially vulnerable communities.28

This gap could widen further. FAIR Plan policies frequently offer limited coverage, fewer carriers are willing to underwrite homes in high-risk regions, and construction costs continue to rise.29 When future disasters strike, these underinsured regions may shift the cost of recovery from insurers to homeowners, communities, and the state, potentially eroding long-term resilience and equity and creating additional fiscal pressure on the state. At the other end of the spectrum, excess and surplus lines have expanded at a rapid pace, offering some solutions to wealthier homeowners who can afford higher-cost coverage from a less regulated market.

Affordability pressures threaten to compound the problem. Homeowners insurance premiums in California remain, on average, below the national average, but the true burden emerges when it is measured against disposable income: The state’s households spent 2.7 percent on insurance in 2024, on average, but that rises to 4.6 percent in the lowest-income zip codes. As premiums climb and options narrow, more households may be pushed toward the FAIR Plan or out of the insurance market altogether. This trend could deepen coverage gaps, limit financial protection, and boost reliance on public recovery funding in future disasters (such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Individual Assistance program and the Small Business Administration’s disaster loan program), which tend to be limited for individuals.30

Actions to strengthen the insurance market

California’s private homeowners insurance market currently faces a total coverage shortfall of $1.35 trillion to $2.00 trillion—the $800 billion to $1.3 trillion private insurance coverage gap for single-family properties as well as the potential FAIR Plan exposure of $550 billion to $700 billion. Within this broader gap, approximately one-third of the total exposure is especially urgent.31 Many of these homes belong to lower-income households that are the least able to absorb losses or to higher-income FAIR Plan policyholders whose needs exceed the plan’s coverage caps.32

Of this high-risk segment, FAIR Plan policies generated about $2 billion in annual premiums as of September 2025, equating to an exposure-to-premium ratio of just 0.28 percent,33 well below the 1.5 to 2.0 percent seen in other high-risk states such as Florida.34 Detailed, granular catastrophe modeling and actuarial analyses would be required to determine the exact ratio. This shortfall suggests that restoring system stability and protecting the most vulnerable homeowners in California may require $8 billion to $10 billion in additional annual premiums—a 50 to 65 percent increase over the current homeowners insurance market.35

But raising premiums alone will not close the gap: As premiums increase, the price elasticity of the demand could cause some homeowners to drop their coverage as it thus becomes more costly. Strengthening California’s insurance market will require targeted efforts to materially reduce risk, rebalance exposure, and attract private capital into high-risk regions. Drawing on lessons from other states and countries, California could consider two strategic areas of focus: improving insurability through active risk reduction and optimizing risk ownership and financing.

Improving insurability through active risk reduction

The state could continue to modernize its infrastructure and building standards (a process begun this year), consider wildfire risk more systematically in land use decisions, and secure more funding for mitigation efforts.

Update infrastructure and building standards. Stakeholders could seek to expand adherence to wildfire-resistant building codes. Homes built according to the state’s Chapter 7A building standards have up to 40 percent lower rates of wildfire loss. However, these guidelines apply only to new constructions,36 and nearly 95 percent of homes damaged in the 2025 Palisades fire were built before Chapter 7A’s implementation in 2008.37 The state could align enforcement across jurisdictions to ensure adoption for all homes.

For existing homes, basic mitigation measures (such as ember-resistant vents and defensible space) can cost $10,000 to $15,000 for a typical 2,000 square foot home, while comprehensive retrofits can be as much as $100,000, depending on the upgrades needed.38 Retrofit solutions with financing mechanisms (for example, Mello-Roos districts or property-based loans and targeted subsidies could help homeowners offset costs and retrofit aging housing stock.) Banks could offer dedicated risk mitigation loans to spread costs over time, which could promote risk reduction.

In addition, the state could encourage insurers to support homeowners’ mitigation efforts through premium credits tied to resilience measures and carrier-funded, property-level risk reduction services. Insurers could collaborate with state stakeholders to jointly develop standardized, verified datasets to track defensible space, home hardening, and Chapter 7A compliance as well as to integrate mitigation into underwriting decisions. For example, Australia launched a Bushfire Resilience Rating Home Self-Assessment app that provides insurers access to granular data to inform discounts.

California has recently taken steps to require its Department of Insurance to periodically review home-hardening and risk-reduction measures. The impact of these efforts will depend on how fully they are integrated into insurers’ rate-setting practices and whether they create meaningful incentives for many homeowners to invest in mitigation.39

Further integrate wildfire risk into land use planning. Some communities, such as Boulder County, Colorado, have incorporated wildfire risk into area planning and zoning updates. Altadena, California, followed suit in April 2025.40 As California seeks to increase its housing stock,41 integrating this consideration into planning decisions can help direct investments toward safer, more resilient areas. Expanded use of risk-informed planning tools, such as wildfire hazard maps, satellite imagery, defensible-space scoring, and land suitability assessments, could help local governments better align growth with long-term resilience.

Increase investments in long-term mitigation and improve coordination across jurisdictions. California currently partners with the federal government to make land less susceptible to wildfires, but estimated additional investment needs range from $5 billion (focused on the highest-risk zones) to $17 billion (focused on expanded treatment zones).42 Consistent funding would enable the state to scale up vegetation management and forest treatment projects, especially in areas where wildland and urban areas intersect.

In addition, past mitigation efforts have faced challenges because of fragmented land ownership, long-term funding commitments, and permitting complexities.43 To accelerate progress, California could explore preapproved treatment zones, expand cross-jurisdictional partnerships, and provide local governments with technical and financial support to implement fuels management. Strengthening collaborative agreements across state, federal, tribal, and private landowners—for example, through shared stewardship frameworks or anchor forest partnerships—may also help overcome coordination hurdles without requiring structural changes in land ownership or governance.

Optimizing risk ownership and financing

Innovative tools and product design have the potential to alter the distribution of risk, improve risk financing efficiency, and increase market stability.

Balance risk ownership through public–private mechanisms. The state’s stakeholders could apply lessons from other models. For instance, California could consider establishing a public–private reinsurance partnership, patterned after some design components of Florida’s Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, as a public backstop for extreme wildfire losses to reduce tail risk, attract private capital, and support private insurer participation in high-risk areas.

Alternatively, California could consider public–private models, similar to the US Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, the UK Flood Re program, and Japan’s Earthquake Reinsurance scheme. California could encourage participation in high-risk areas by applying a predefined, layered risk-sharing structure, in which the state would be responsible for the most extreme losses in the plan—a portion of which would ultimately be covered by all taxpayers over time. This initiative could complement the existing California Wildfire Fund, which reimburses eligible claims arising from wildfires caused by utilities. Recently, the state has moved to expand this fund and commissioned a review of broader catastrophe-financing models to distribute future losses more equitably across stakeholders.44

Foster innovation in insurance product design. Emerging models that reward proactive risk reduction could be further explored. For example, a novel wildfire-resilience insurance policy offers lower premiums and deductibles by linking pricing to ecological forest-management practices that help mitigate fire risk.45 These types of policies reinforce the value of coordinated land management, provide a potentially scalable path to maintain coverage in fire-prone zones without expanding building restrictions, and create a space for insurers to explore new products that reflect community-level risk reduction.

Attract alternative capital to expand coverage capacity. Index-based financial products such as catastrophe bonds (used by states such as Florida and Louisiana) and parametric insurance (part of Boulder County’s wildfire pilot and New York City’s flood program) could increase access to capital markets, enable faster payouts, and reduce reliance on traditional indemnity-only models. Their adoption in California has been limited by challenges in accurately modeling wildfire frequency and severity as well as by the basis risk inherent in parametric design, which employs an externally measurable event, independent of loss, to trigger insurance payments. More granular, real-time data coupled with models that use this information to more accurately estimate uncertainty could help unlock the full potential of these instruments.

Potential next steps

As a starting point, stakeholders could pursue three steps to chart a path for California’s homeowners insurance market:

- Quantify total cost of risk. Gaining alignment on the total cost of risk could offer a valuable lens when assessing potential levers. This analysis could focus solely on wildfires or include all natural disasters to support more informed capital allocation decisions. How much is at stake, in which areas, and why?

- Prioritize risk reduction investments with higher economic return or social impact. Stakeholders could assemble a portfolio of risk reduction actions and prioritize them using criteria such as defined return on investment, required investment, feasibility of implementation, and time to impact.

- Evaluate risk financing and residual coverage options and implement a comprehensive solution. Stakeholders could identify and assess mechanisms to expand the financing of residual risk, particularly for properties that are unlikely to be served by the private market under current conditions. Stakeholders could also define optimal models based on affordability, risk transfer efficiency, and long-term sustainability, among other factors. Increased transparency on the roles of public and private entities in sharing extreme loss risk could help stabilize expectations and reduce uncertainty about who ultimately bears the cost.

California stands at a pivotal moment in its efforts to stabilize its homeowners insurance market. The growing frequency and intensity of natural disasters have exacerbated longstanding structural challenges, including underpriced risk, inadequate capital, limited coverage options, and a segment of households that can’t afford insurance. Left unaddressed, these issues could compound over time, placing greater financial pressure on households, insurers, and the state.

Building a more stable and resilient insurance market, which supports economic growth and social balance, will likely require a combination of sustained, large-scale investment in risk reduction and updated mechanisms for financing and catastrophic risk sharing. Together, the considerations outlined here could better protect communities, stabilize the market, and position California as a global leader in climate adaptation for wildfire-prone regions. Given the pace and scale of recent wildfire events, the urgency to act has never been greater.